ROHATYN | JEWISH STONES UA

ROHATYN | JEWISH STONES UAJews were present in Rohatyn since the 15th century, and settled as residents in Rohatyn as early as the middle of the 16th century. The Jewish community formed an integral and dynamic part of Rohatyn life for four centuries, until the Holocaust. In 1633, the Jewish community of Rohatyn was granted privileges by the Polish king Władysław IV Waza, giving them municipal rights to build a synagogue and a cemetery, and to trade. Over time the community grew and diversified; during the late Austrian era (second half of the 19th century) when Rohatyn was part of the Kingdom of Galicia, the town's more than 3000 Jews comprised over 40% of the total population of Rohatyn and its adjacent village of Babintsi.

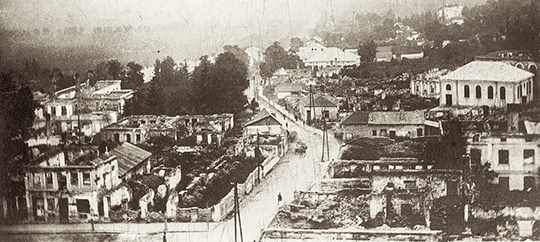

During World War I, Rohatyn was engulfed in battles of the eastern front and alternately occupied by Russian forces and the allied armies of Austria-Hungary, Germany, and the Ottoman Empire. In two waves of the shifting front during the first year of the war, the town was burned by the retreating Russian army, destroying most of Rohatyn's building stock including Jewish homes and synagogues. During the second retreat in 1915, Russians forcibly deported more than 500 Jewish men from Rohatyn to Kyiv and then to Chembar (Belinsky), Russia); the men were unable to return to Rohatyn until 1917. From 1916 the Central Powers armies led by Germany established a military camp and training center outside of Rohatyn, where they remain as reserves behind the front line for most of the rest of the war. A number of Rohatyn Jews served in the Austro-Hungarian army during this time, until the defeat of the Central Powers in the west and the collapse of the three empires in the alliance.

After WWI and residual regional conflicts, all of Galicia became part of the Second Polish Republic, and Rohatyn's Ukrainian, Polish, and Jewish communities began rebuilding the town; the Great Synagogue was rebuilt from its ruined shell, and Jews rebuilt the market square and their homes from the rubble left by the fires. With modernization the Jewish community further diversified, now represented by Rabbinic, Hasidic, and secular Jewish families, and a growing interest especially among the young in the Zionist movement.

During the Soviet occupation of Rohatyn from September 1939, Jewish ownership of businesses largely ended, and Communist administrators arrested, tried, and deported wealthy Jewish families and politicians. With the German occupation of the town from July 1941, the Holocaust in Rohatyn began. One of the earliest Jewish ghettos in the region was formed in Rohatyn, imprisoning thousands of Jews from Rohatyn and eventually incorporating Jewish communities from many of the surrounding towns and villages. A series of German aktions in Rohatyn destroyed thousands of local and regional Jews at two mass killing sites on the edge of the town , and deported more than a thousand more from Rohatyn to annihilation at the death camp at Bełżec . Of the ghetto population in the several thousands, fewer than 200 Jews survived in hiding in Rohatyn and the forests for the three years of German occupation.

Only a handful of the Jewish survivors remained in the region after liberation; most emigrated to Mandatory Palestine (later Israel), western Europe, the United States, South America, Australia, and other distant places. There they joined prewar émigrés and started new families, creating a new global Rohatyn Jewish community.

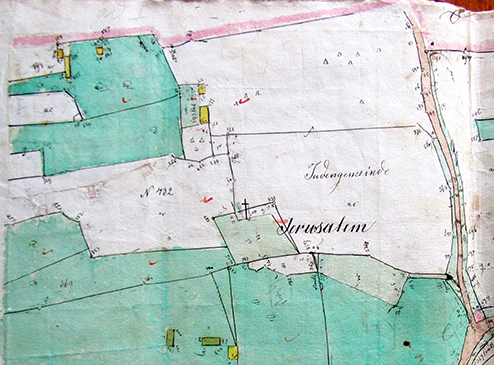

Rohatyn still has two Jewish cemeteries , known informally as "old" and "new". The first or "old" Jewish cemetery was likely begun very soon after the Jewish community of Rohatyn was granted rights in 1633, so is now nearly 400 years old. It was originally established outside of the residential areas of Rohatyn and Babintsi , though as the settlements grew over the centuries the site has become incorporated into the fabric of the city. The site is shown and labeled on an 1846 Austrian cadastral (tax parcel) map sketch, adjacent to a mound locally known as "Jerusalem hill". Although the cemetery is fairly large (about one hectare), archival records of Rohatyn municipal proceedings indicate that by the early 20th century the cemetery had run out of space for burials, and the Jewish community intended to expand the cemetery onto land it had previously purchased. Objections to that expansion from cemetery neighbors and an extended legal conflict ended with a decision to seek new land elsewhere for future burials; this separate land became the "new" cemetery.

The second or "new" Jewish cemetery was established near the northern edge of Rohatyn sometime in the first decades of the 20th century, in an area which at the time had almost no residences. This site is smaller than the "old" cemetery, and because it was in service for only a few decades before the Holocaust, it likely has a much smaller number of prewar and wartime burials, though one Jewish memoir mentions a mass grave there also. The cemetery does not appear on any known prewar city maps (typically the maps do not extend north to the cemetery), but it is clearly visible in a 1944 aerial photo of Rohatyn taken by the German Luftwaffe during their retreat westward. The aerial photo demonstrates that the current fenced boundary of the cemetery is smaller than the site's original boundaries, but it is not clear whether there are any Jewish burials outside the fence.

No burial records for either of the Rohatyn Jewish cemeteries have survived. WWI-era photographs and a 1930s film of the "old" cemetery show remarkably dense arrays of tall Jewish headstones – almost none of which still remain today. During the German occupation of WWII, and possibly also during the postwar Soviet era, nearly all of the headstones in the cemeteries which had marked the graves of Jews for hundreds of years were removed and used as construction materials for roads, new building foundations, and other masonry and fill purposes, mostly disappearing under street surfaces and building facades. The cemeteries were practically denuded of markers, and with them the physical memory of the Jewish community was destroyed at the same time.

In the 1990s survivors and descendants of Rohatyn Jewish families joined to reestablish the two cemeteries as memorial spaces, fencing the boundaries and erecting memorial stelæ to commemorate the Jewish community and its destruction. Today the cemeteries are owned by the Rohatyn civil community, and both the "old" cemetery and the "new" cemetery are regularly maintained by Rohatyn Jewish Heritage in cooperation with the Rohatyn City Council and funded by donations from Rohatyn descendants and other interested people.

Efforts to recover displaced Jewish headstones in Rohatyn began almost as soon as Jewish survivors could return to the town after Ukraine gained its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Fishel Kirshen led and funded most of the early efforts, in partnership with local teacher Mykhailo Vorobets, a longtime activist in the multicultural history of Rohatyn. By the time Kirshen passed away before 2011, the "old" Jewish cemetery had about ten intact or broken standing headstones and a similar number of loose headstone fragments and grave covers, while the "new" Jewish cemetery had three intact standing headstones, about ten mostly-intact downed headstones, and about 25 loose fragments.

In 2011, Rohatyn Jewish Heritage joined with the Rohatyn District Research Group to fund and coordinate Jewish headstone recovery in the town, renewing the partnership with Mykhailo Vorobets for local communication, labor arrangements, and payments. For more than a decade, recovery efforts by townspeople, by the City, and by Rohatyn Jewish Heritage and its volunteers, have gathered more than 500 headstone fragments and an occasional intact headstone from around the city and returned them to the "old" Jewish cemetery for safekeeping. Rohatyn residents have assisted the effort by reporting discovered headstones and in some cases even moving individual stone fragments to the "old" cemetery themselves.

From the long history of the Rohatyn Jewish community and the known size of its population, it is evident that the recovery work to date, while significant, represents a very small percentage of the total number of headstones which once stood in the two cemeteries. It is thus expected that the recovery work will continue for decades to come.

No comprehensive project to document all of the standing and recovered Jewish headstones in Rohatyn has been organized to date, although photographic documentation of standing headstones and the first recoveries in 2011 was made by Dr. Alexander Feller and Jay Osborn for the Rohatyn District Research Group in 2011, and partial documentation of subsequent recoveries since then has been made by Rohatyn Jewish Heritage. The database project on this website will enable organization of the partial data already available and a scheme for collecting more complete data on the larger set of recovered stones in the future, as time and war conditions allow.

-

Wikipedia:

Rohatyn (English)

Rohatyn (Ukrainian)

- Category: Judaism in Rohatyn; image collection on Wikimedia Commons, including subcategory Jewish cemeteries in Rohatyn

- Rohatyn District Research Group (RDRG), an online resource and discussion group for Jewish descendants of Rohatyn

- Rohatyn Jewish Heritage, a Ukrainian NGO working to preserve the physical heritage of Rohatyn's lost Jewish community

- A History of the Jewish Community of Rohatyn , on the website of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage

- The Jewish Population of Rohatyn , on the website of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage

- The Yizkor Book for Rohatyn: Kehilat Rohatyn v’hasviva , on the website of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage, with links to an online original (image) version hosted by the NYPL, and an online translated (English) version hosted by JewishGen

- Jewish Cemeteries of Rohatyn , on the website of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage

- Jewish Grave Markers: Lost and Recovered , on the website of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage

- Old Jewish Cemetery Rehabilitation Project , on the website of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage

- New Jewish Cemetery Rehabilitation Project , on the website of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage

- Jewish Headstone Recovery Project , on the website of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage

- Mapping Rohatyn: 1846 Cadastral Map , on the website of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage, based on a digitally stitched version of the historic map sheets created for the RDRG and Gesher Galicia

- Mapping Rohatyn: 1944 Aerial Photo , on the website of Rohatyn Jewish Heritage, based on an image sourced from NARA by the RDRG