DOBROMYL | JEWISH STONES UA

DOBROMYL | JEWISH STONES UA

Brief histories of the Dobromyl Jewish community are available in the 1964 Memorial Book of Dobromil (Sefer zikaron lezekher Dobromil) and in texts and online publications researched by the Ukrainian historian Mykhailo Kril. The settlement of Dobromyl (Dobromil in Polish) is first mentioned in records in 1374; the first record of Jews in the town came less than two centuries later, and by 1566 a wooden synagogue had been built on the west side of the market square; a large stone synagogue, known as the Great Synagogue, was erected adjacent to the wooden one in 1591. Initially, Jews lived away from the town center but over time more settled around the square and especially just north and northwest of the center. In 1662 there were barely 120 Jewish residents, mostly very poor, but by the early 1700s there were about 1250 Jews in Dobromyl, making up more than half of the town's total population.

In the 16th through 18th centuries the Jewish community was granted selected privileges several times by Polish kings, the regional landowning Lubomirski family, and the local land-owning Herburt family; these privileges included the right to self-administration through a kahal, the right to establish a cemetery, and rights to practice certain trades, along with certain obligations and restrictions.

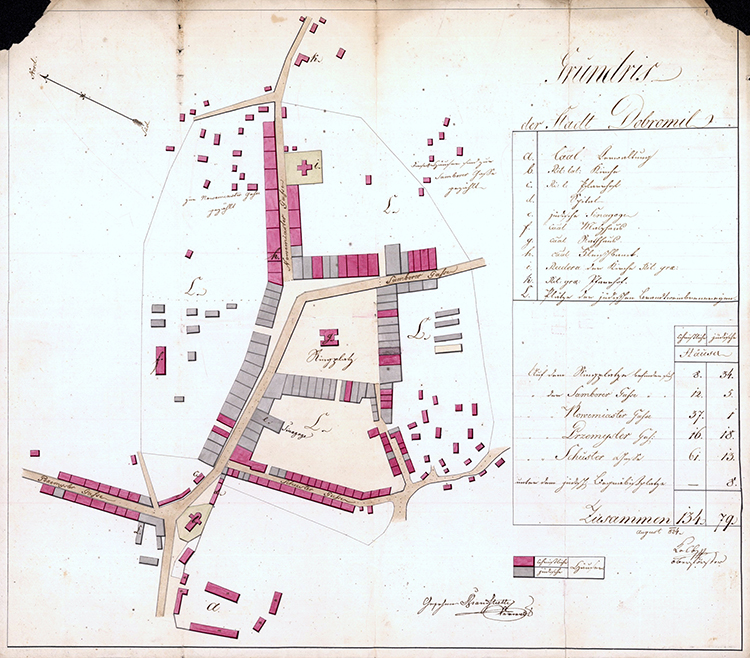

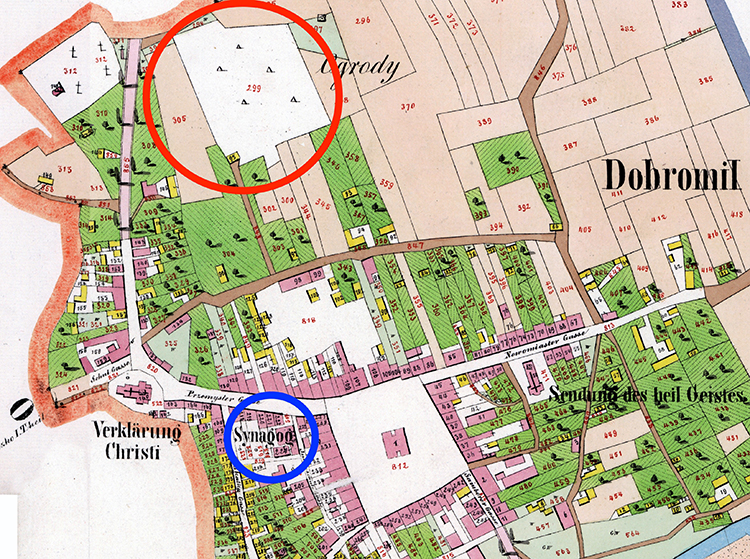

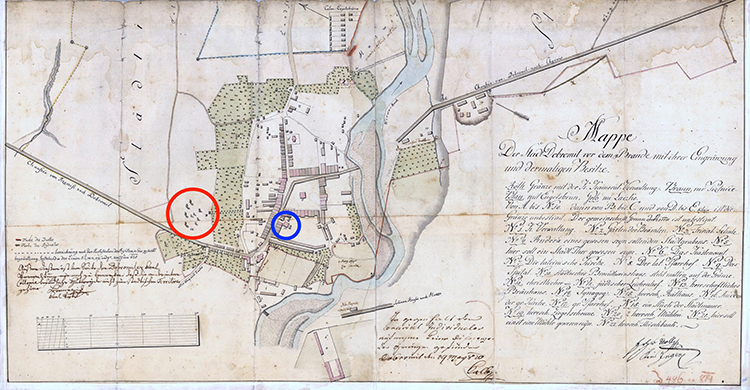

Over time Dobromyl was plagued by a series of fires, especially in the adjacent German colony of Engelsbrunn, but was repeatedly rebuilt. An Austrian town layout from 1824 shows the main buildings of the center and along roads radiating from the market square; 79 Jewish homes and service structures are shown colored grey (and the large synagogue is labeled), while 134 non-Jewish buildings are shown colored red. High-scale Austrian regional maps from later in the 19th century as well as Polish maps from the interwar period schematically show the market square with symbols marking churches, the Great Synagogue, and both Jewish and Christian cemeteries.

After World War I, life for Dobromyl Jews now in the Second Polish Republic evolved much as it did elsewhere in former eastern Galicia, marked by increasing engagement with Zionism and Jewish youth groups, educational and professional opportunities for women, a Macabee sports club and Jewish football team, further secularism and even mixed marriages, plus participation in national politics but also increasing restrictions and quotas in some trades.

The invasion of Poland by Germany in 1939 did not physically endanger Dobromyl's Jewish community, though there were economic impacts for the wealthiest Jews once the town was occupied by the Soviets. Initially, Jews were surprised and pleased to hear some Soviet soldiers and officers speaking Yiddish, and the town accepted hundreds of refugees from Przemyśl who had been deported by the German Einsatzgruppe I.

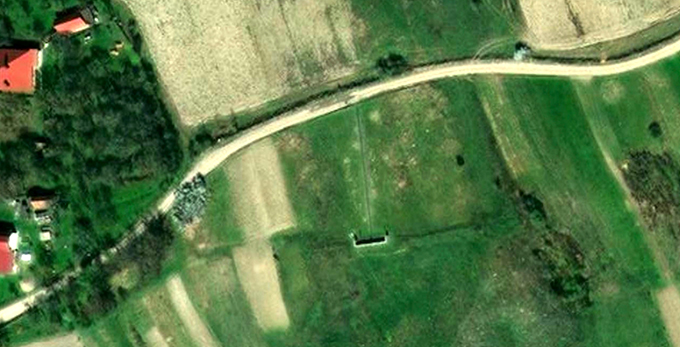

The Jewish cemetery of Dobromyl in the Lviv oblast of Ukraine is located on a hill among fields north of the town center; the cemetery entrance is approximately 500m north of the Dobromyl city council office on an unnamed road east of T1418 and the Christian cemetery. A lapidarium-style Wall of Memory monument now marks the site, located at GPS 49.57544,22.78356.

The first written record of the cemetery dates from 1612. The cemetery appears on an Austrian-era cadastral map from 1852 with its boundaries at that time precisely outlined (land parcel 299). That map and another from 1814 (documenting the rebuilding of the town after a fire) show a road or allée (a tree-lined path) running up the hill from the former Jewish quarter of Dobromyl; according to Mykhailo Kril, that road (no longer extant) was locally known as ulica Martwa (Dead Street).

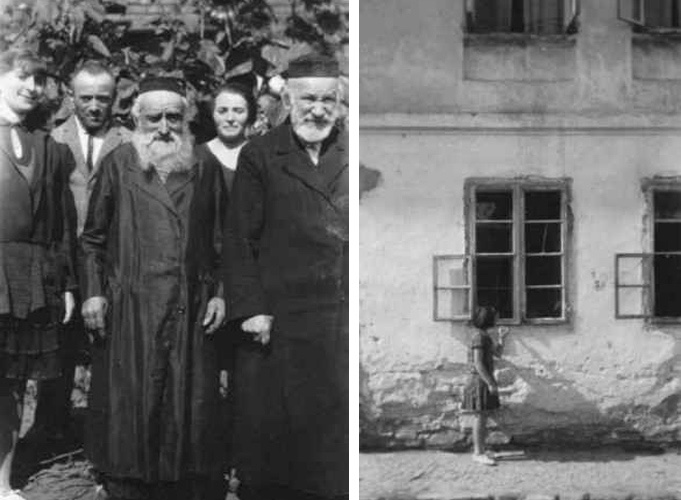

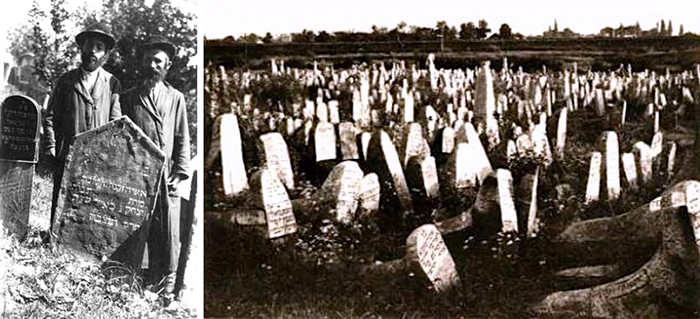

No cemetery records have survived, but it is reasonable to assume from preWWII census data that there have been several thousand burials there of Jewish residents both from Dobromyl itself and from the surrounding villages. Two prewar photos taken in the Jewish cemetery are known to exist: one from 1929 showing two Jewish men standing behind the headstone of what is probably a relative (from the Dobromyl Yizkor Book), and the other a much broader image from 1937 (from Mykhailo Kril's 2017 online article) showing hundreds of stones in a great variety of sizes and shapes. This latter image gives a painful clue to what has been lost in Dobromyl.

In the 1964 Memorial Book of Dobromil (Sefer zikaron le-zekher Dobromil), Walter Artzt reported that during the German occupation of the town the Jews were dragged to the cemetery, made to pull out the matzevot, carry them into town, and pave the streets with them. The IAJGS International Jewish Cemetery Project entry for the Dobromyl cemetery indicates that at the time of the survey in 1996, the cemetery boundaries marked a space which was smaller than in prewar times, and only 1 to 20 tombstones were present, none in their original location.

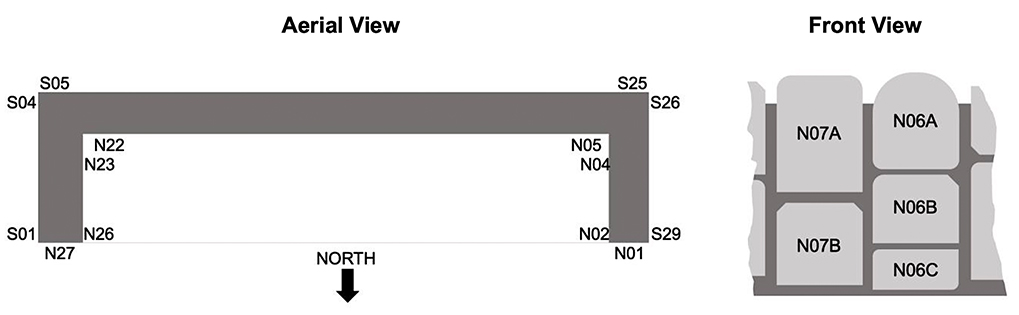

Photographs of the recovered headstones as installed in the Wall of Memory were taken in 2017, 2019, and 2023 by Sasha Nazar and Jay Osborn on behalf of the Sholom Aleichem Society of Jewish Culture in Lviv. Working from photographs, Gerald Pragier transcribed the Hebrew/Yiddish epitaphs and then translated them into English, adding explanatory footnotes where deemed appropriate. See his methodological notes on the interpretation of the Dobromyl gravestone inscriptions for English readers. Thereafter, Sasha Nazar and Tetiana Fedoriv provided the parallel Ukrainian translations for these Dobromyl gravestones.

-

Wikipedia:

Sasha Nazar at the Wall of Memory in the Jewish cemetery in Dobromyl. Source: Rohatyn Jewish Heritage.

Dobromyl (English)

Dobromyl (Ukrainian)

Dobromyl Synagogue (Ukrainian)

- Category: Jewish cemetery in Dobromyl; image collection on Wikimedia Commons

- Dobromyl, Ukraine, on the website of JewishGen KehilaLinks

- Memorial Book of Dobromil (1964) (Sefer zikaron lezekher Dobromil), English text only of the Yizkor Book in the JewishGen Yizkor Book Project

- Dobromil: Zikhroynes fun a shtetl in Galicia in di yorn 1890-1907 (Dobromil: Life in a Galician Shtetl, 1890-1907) (1980); edited by Saul Miller, image copy in the New York Public Library Digital Collections

- Dobromil: Life in a Galician Shtetl, 1890-1907; English version hosted online in the JewishGen Yizkor Book Project

- Star of David, or Last Song of Shofar; a memoir novel by Ludmila Leventhal on the experiences of her father Shmuel Leventhal before, during, and after WWII in Kwaszenina and Dobromil; Star of David Press, Boston, 2006

- In the Valley of Vyrva, Vol. 3: A Brief History of the Jewish Community of Dobromyl; Mykhailo Kril, from the series Father's Land, 2016

- Facebook post with photos of the headstone recovery effort, 7 March 2016, on the page of Roman Tsytsyk

- Facebook post with photos of the dedication ceremony for the Wall of Memory, 14 June 2016, on the page of Sasha Nazar

- "9 червня у Добромилі на місці єврейського цвинтаря відкриють Стіну Пам’яті" (On June 9, the Wall of Remembrance will be opened in Dobromyl on the site of the Jewish cemetery); notice 06Jun2016, on the internet magazine Добромильський Край (also on the Internet Archive )

- "Відкриття Стіни Пам’яті на єврейському цвинтарі у Добромилі" (Opening of the Wall of Remembrance at the Jewish cemetery in Dobromyl); Pavlo Bishko and Evelina Krupa, on the internet magazine Добромильський Край (also on the Internet Archive )

-

"Пам’ятні місця євреїв Добромиля" Sketch 1846 (Memorial Sites of the Jews of Dobromyl); Mykhailo Kril, 13Jan2017, on the internet magazine Добромильський Край (also on the Internet Archive )

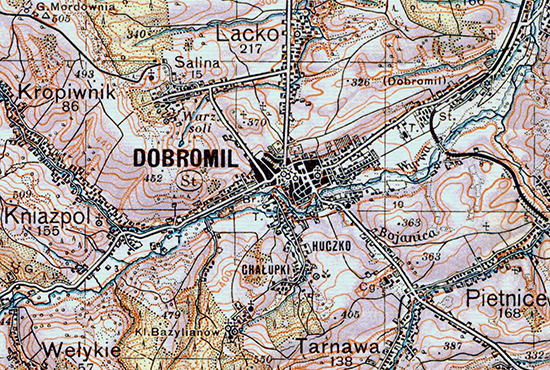

Excerpt from a 1938 topographic map showing Dobromyl and surrounding villages; the Jewish cemetery and synagogue are marked with T symbols. Source: Polona. - Lviv Oblast: Identified Jewish Cemeteries, on the website of A Guide to Jewish Cemetery Preservation in Western Ukraine

- Dobromil Jewish Cemetery, cemetery survey and description on the website of ESJF (European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative)

- Dobromil, cemetery description on the database of the International Jewish Cemetery Project

- Dobromil – JewishGen Online Worldwide Burial Registry (JOWBR), a cemetery description and a database of photographs and about 120 English-language names and dates transcribed from headstones in the Dobromyl Jewish cemetery in 2024 for Jewish Stones UA

- Dobromil Cadastral Map 1854, on the website of Gesher Galicia

- Dobromil PAS 50 – SŁUP 35 – I (1938), a map at 1:100,000 scale of the terrain around Dobromyl, on the website of Polona (via the Polish Biblioteka Narodowa and the Wojskowy Instytut Geograficzny) via the WIG Archive and the US Library of Congress

- Mappe der Stadt Dobromil vor dem Brande mit ihrer Eingränzung und dermaligen Bestize 1814 (Map of the town of Dobromil before the fire with its boundaries and current layout); record number 29/663/0/6/586, a map of the town showing buildings including the Great Synagogue and land parcels including the Jewish cemetery, from a paper map and digital scan by the Archiwum Narodowe w Krakowie

- Grundris der Stadt Dobromil 1824 (Layout of the Town of Dobromil); record number 29/663/0/6/587, a sketch of buildings in the downtown color-keyed by Jewish and non-Jewish owners, from a paper map and digital scan by the Archiwum Narodowe w Krakowie

- W Dobromilu, ogólny widok (1903); postcard view of Dobromyl and the hills to the north by the photographer Abraham Türk, on the website of Polona (via the Polish Biblioteka Narodowa)

- Dobromil, in the Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933-1945, Volume II: Part A, pages 500~501, by the USHMM (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

- Nationalsozialistische Judenverfolgung in Ostgalizien 1941-1944: Organisation und Durchführung eines staatlichen Massenverbrechens (National Socialist persecution of Jews in Eastern Galicia 1941-1944: Organization and execution of a state mass crime); Dieter Pohl; Studies in Contemporary History, Volume 50; Institut für Zeitgeschichte, Munich, 1997; pages 67~68, 236

- Deutsche Herrschaft, ukrainischer Nationalismus, antijüdische Gewalt: Der Sommer 1941 in der Westukraine (German rule, Ukrainian nationalism, anti-Jewish violence: the summer of 1941 in western Ukraine); Kai Struve; Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston, 2015; pages 216~234, 245~246, and many others

- "The Wall of Memory for the Jews of Dobromil"; Arthur Kurzweil, in the March 2023 issue of The Galitzianer, the quarterly research journal of Gesher Galicia